A tribute to Tony Bilson – chef, writer, artist

I remember the legendary chef Tony Bilson walking to meet me in Surry Hills for the first time. Physically he was probably only half the man he used to be. “Cancer,” he said, like it was something to be exasperated by. Then with a hard breath he guided me up the street to a corner café where we spoke for quite some time and with quite some intensity.

Tony reminisced about when Brett Whiteley lived down the road, discussed the latest phase of his medical treatment, empathised with me about the struggles of fatherhood, veered into the problems he’d had with alcohol and how glad he was to have put it behind him, and reflected on Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin and the nature of addiction and how creative people “tend to be the most vulnerable people”. There was real feeling to the way he said the last few words; a note of friends lost, but not forgotten.

He then spoke to me at length about Zen Buddhism and ‘kaiseki’, a form of cooking from Japan which he described as, “A love poem to the rhythm of life. It’s all about eating the seasons.”

When he said the last few words, Tony leaned in close and cupped his hand as if it were holding a pebble in it. He explained to me that Zen monks would place a warm stone near their bellies to ward off hunger. I did not grasp the full nature of it, only that kaiseki had arisen from this history: simple, pure, spiritual.

News of Tony’s death “from a complicated set of illnesses” at the age of 76 made me sad now for not seeing more of him than I did. Never enough time; then no time at all.

When we met over that imaginary ‘kaiseki’ meal in late 2017, he had just signed on to become the chief food critic and columnist for Neighbourhood, the monthly Sydney newspaper I was editor of.

I was not unaware that getting Tony Bilson on board was a major coup for an independent entity like us. He was the much feted ‘Godfather of Australian Cuisine’. The man who had pioneered French gastronomy here with a contemporary flair and signature artistry that made him a figure of world renown.

Tony’s moustache and goatee beard set me in mind of The Three Musketeers. The look signalled the energy within despite his ill health; a playfulness and sharpness that could rise quickly in conversation.

I mentioned a famed food writer noted for his opinionated and idiosyncratic style. Tony told me he had no desire to imitate him. “I sat on a panel with him at one of those festivals,” he said scathingly. “He was an arsehole. I told him so too. And I don’t want to spend my time being in the company of arseholes, or acting like one.”

Okay. Got it. Let’s not do that type of column!

Born on 5thJanuary 1944, Tony dated his love of food and fascination for cooking back to early boyhood when he said he instinctively knew he wanted to be chef. By the time he was 20, however, he found himself working in Melbourne in banking. The sudden loss of his mother in 1963 awakened him to his true vocation: “I just thought fuck this, I am going to be a chef. And that was it.”

His father Jack had died in a car accident when Tony was just four years old. His mother Evelyn remarried a local Colac store owner, Bob Bilson, who would adopt Tony and his three younger siblings and gift them the family name (Tony’s birth name was Ernest Anthony Marsden; his cousin was the lawyer and gay rights activist John Marsden).

Sent away to study at Melbourne Grammar, he’d eventually be taught art by the painter John Brack. He vividly recalled Brack being pulled up by the school principal for inciting the students to be artists rather than just teaching them about art. It was a lesson Tony absorbed very much in Brack’s favour.

After school, Tony would visit Balzac and linger in the company of the restaurateur owners, Georges and Mirka Mora, who had the painter Charles Blackman working in their kitchen. Tony would fall under the influence of the art patrons, John and Sunday Reed, who dined there. After seeing the classic film Les Enfants du Paradis (1945) multiple times and forming a crush on the actress and ‘60s pin-up Brigitte Bardot, his Francophile passions bloomed.

But it was Georges Mora’s copy of a 1903 book by August Escoffier, the iconic French chef, that gave Tony a profound sense of culinary history. He saw that one great individual could bring about changes in cooking and ingredients and the way food was prepared, as well as how a kitchen was organised and the technology that was used, not to mention the rituals of a meal itself. Tony was fond of nuggets of Escoffier wisdom like “the greatest dishes are very simple”, “good food is the foundation of happiness” and “people who do not accept the new, grow old very quickly”.

After paying his dues as an aspiring chef in Melbourne, Tony and his then partner Gay Morris headed to Sydney and launched Tony’s Bon Gout on Elizabeth Street in Surry Hills. It was here that the Sydney Push (Germaine Greer, Richard Neville, Margaret Fink and friends) and the arts circle around gallerist Rudy Komon (who lent Tony pictures to hang on the walls) mingled with leading ALP figures of the early 1970s.

It’s said Tony showed Sydney politicians they could meet somewhere other than the pub or a restaurant in Chinatown. Later, he’d be appalled at the way the ALP lost direction, with a new generation of professional politicians who had pretensions of ‘class’ but no understanding of real class at all.

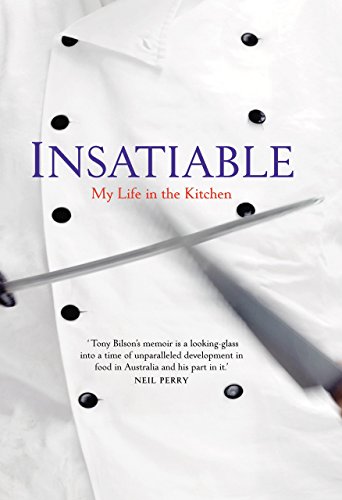

He noted in his memoir Insatiable how the media magnate Kerry Packer visited Bon Gout and demanded a well-done T-bone and a can of Coke for lunch, neither of which were on the menu. Mr Packer was not a man to brook refusal. So, they cooked him a well-done steak and sent out to the pub for a Coke – to keep Kerry happy.

The couple’s next move in 1975 was a daring one, kicking off a world-class restaurant outside of Sydney, accessible by boat only, at Berowra Waters Inn on the Hawkesbury River. Tony had the premises redesigned by his friend, an innovative architect by the name of Glenn Murcutt. As Tony said in Antony Jeffery’s book, Many Faces of Inspiration, “I always loved the idea of taking people out of their normal space and going through a psychological gap and getting a reward that creates memories.”

He would leave Berowra in 1982 after a difficult separation from Gay with whom he had two daughters, to become the founder of Kinselas in partnership with another adventurous friend, the property developer Leon Fink. The pair renovated the old three-storey funeral parlour at Taylor Square, transforming it into a theatre, music and dining venue. Tony was particularly inspired by Le Chat Noire café that Toulouse-Lautrec and other bohemians of the 1890s had once frequented in Paris.

At Kinselas, Tony would train and mentor Tetsuya Wakuda, one of the many young chefs he encouraged on the way to greatness. Tony was forging a strong interest in blending French and Japanese culture in the kitchen. His approach would resonate globally, all the way back to France, though he’d simply say to SBS that “cooking is a group activity in the kitchen and I think we all pass on [things] to each other.”

It’s hard to recall an era when someone who loved the idea of bringing a community together over good food and wine was more of a giant than those currently developing their branding on Instagram and boosting their TV ratings. But Tony Bilson was a very different personality from what we now identify as a celebrity chef.

It’s telling that what he most liked about working with Tetsuya was “his modesty and quietness, a kind of privateness”. Not for Tony Bilson the hysterics and abusive theatre of the modern-day chef. He preferred to compare cooking to poetry, “it’s just another way of opening up beauty and culture to people.” For him, the culinary changes he drove were simply an embrace of the multicultural changes already happening in Australian society.

Quite apart from his finesse and creativity as a chef, he was a technical and organisational innovator. Tony’s historical understanding of his art helped him to change everything here from food storage practices to pioneering new techniques in slow-time cooking, as well as the way in which professional kitchens were structured and run. It’s almost impossible to limit his influence on what we now take for granted as a modern Australian restaurant of any quality.

After Kinselas, he would go on to found a series of acclaimed dining venues, among them Bilson’s at Circular Quay, Fine Bouche, The Treasury at Sydney’s Inter-Continental, Ampersand and Bilson’s at the Radisson Plaza, but his focus on being a great chef and an aesthetically subtle host cost him dearly in business.

Tony would have another son and daughter with his beloved wife Amanda, whom he married in 1986. Amanda would be his soul mate and the sounding board for all his thinking over the next four decades. Their relationship would keep him buoyant no matter the challenges before him.

In a 2009 interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, Tony reflected on his mercurial career with a typically raw honesty. “It can be soul destroying,” he told the journalist Winsor Dobbin. “Some of the failures I’ve had have been as a result of the breakdown of a relationship, others through my own alcoholism; some have been wrong place, wrong time. Some were fantastic successes creatively but didn’t make huge amounts of money. Something like Kinselas could only have come from an alcoholic’s imagination. The distress a failure causes other people – the feeling you’ve let people down – is the worst.”

It was perhaps a premonition of more troubles to come. He’d go bust when his last venture, the much-loved Bilson’s Restaurant, and its sister venue Number One Bar, both of which he had set up independently with Amanda, was hit by an astronomical tax bill in 2011. Then he’d have to fight cancer and come back from the battle. Which is about the time I met him.

Our relationship began via email and a series of calls. I’d quake when dealing with him over the phone. Around the Neigbourhood office, I had affectionately nick-named him ‘Big Tony’. When Big Tony was on the line I felt I’d better be paying attention. Naturally, I was taken aback at how physically frail he was when I finally met him. He was still an unmistakable force of nature, and just the tiniest bit intimidating, but there was a genuine softness to him that I had also not anticipated from our calls.

Tony told me he liked Neighbourhood because it reminded him of the Village Voice in New York.

“Brett would have loved it. We have to build a community. I really want to be a part of it.” I was struck by his royal use of ‘we’. It was like having an inspiration session at half-time with the coach – and being sent back out to fight for victory in the second half despite the odds being stacked against you. Neighbourhood Paper was an independent wild card in the media landscape. And Tony was all for it. He was less keen to discuss writing a food column in any way I’d half-imagined, and was full steam ahead for cultural change and what sounded close to a revolution in consciousness. “We have to show them what’s possible.”

He’d invite me over to his apartment with Amanda, who was caring for him as well as working as personal assistant for the broadcaster Phillip Adams. The names that ran familiarly from Amanda and Tony’s lips were a gallery of artists, politicians, poets, musicians and chefs who had defined our cultural history: John Olsen, Neville Wran, Robert Adamson, Tetsuya Wakuda, or “Tets’ as Tony liked to call him.

Their home was quite modest, filled energetically with books and paintings. At Tony’s request, Amanda fished out a beautiful art-book on ‘Kaiseki’ that he had told me about. A quality to the photography gave off the impression that the food was almost lit from within.

Tony sat deep in his chair perusing the pages, his light beard and moustache and slightly wild hair adding up to a literally electrifying presence despite the illness that ravaged him. Staring at Tony as he spoke, I thought of a great king in a Shakespearian tragedy I could not name, full of wisdom and wily humour, raging against the dying of the light and refusing to give up the throne without going into battle as he had always done. He was ready to write another column; there was food and poetry to celebrate. It was time again to eat the season.

– Mark Mordue ©

Tony Bilson is survived by his wife Amanda Bilson and their daughter and son, Lily and Edward, and his two daughters Jordan and Sido from his previous relationship with Gay.

Beautiful Mark!

LikeLike

he is not dead

LikeLike